In an art critical context, it does not make sense to seek a lineage in what we categorize as “appropriation art” that predates Marcel Duchamp’s readymade gesture. Dating here is an issue, as it’s not possible to see this gesture as having been understood prior to Duchamp’s Pasadena show in 1963. But dating aside, there is no need for confusion, for it is possible to be very clear: appropriation is not simply the borrowing of a style. Neither is it the borrowing of an object: for example, it is not the pasting of newspaper cuttings into a cubist composition, to occupy the place of a signifier. Nor has it anything to do with stealing (there is a difference between putting on a Shakespeare play and asserting that you wrote it). Appropriation art involves the isolation of a discrete object, a “found” object (in the widest possible sense), in order to re-contextualize that object.

This recontextualization finds its justification in the presentation of the object anew. To throw new light upon objects has always been the primary goal in the history of what we now term contemporary art. Sherrie Levine’s Walker Evans photographs may appear to be an end-point of such practice, but in effect, the gesture is “almost the same” as Duchamp’s. Her goal is also to (to use Duchamp’s words) create “a new thought for that object.”

For the eleventh exhibition at Essays and Observations, we have invited Johannes Regin, Jonathan Monk, Michalis Pichler, Pierre-Olivier Arnaud, and Roisin Byrne to present positions on appropriation that help to circumscribe the sometimes not so obvious limits of this artistic strategy.

—

Den Ursprung der Kunst, die wir heute als Appropriation kategorisieren, zeitlich vor Marcel Duchamps Readymade-Gestus zu verorten, macht wenig Sinn. Auch wenn eine genaue Datierung hierdurch schwierig wird, da dessen Relevanz nicht vor Duchamps Ausstellung 1963 in Pasadena verstanden wurde. Doch von der Datierung einmal abgesehen, lässt sich sehr klar sagen: Appropriation ist nicht einfach die Übernahme eines Stils. Auch geht es nicht darum, lediglich ein Objekt zu entlehnen: wie es beispielsweise bei einer kubistischen Komposition der Fall ist, in die ein Zeitungsschnipsel, der hier als Signifikant dient, geklebt wird. Bei Appropriation Art handelt es sich darüber hinaus nicht um Diebstahl (ein Shakespeare-Stück aufzuführen und zu behaupten, man habe das Stück selbst geschrieben, ist etwas anderes). Appropriation erfordert die Isolation eines einzelnen Objekts, eines “gefundenen” Objekts (im weitesten Sinne), mit dem Ziel, dieses Objekt zu re-kontextualisieren.

Diese Rekontextualisierung findet ihre Berechtigung in der neuerlichen Präsentation des Objekts. Andere Facetten von Dingen sichtbar zu machen war stets das primäre Ziel in der Geschichte zeitgenössischer Kunst. Sherrie Levines Walker Evans Fotografien mögen hier wie ein Endpunkt dieser Praxis erscheinen, doch tatsächlich ist auch ihre Geste “fast identisch” mit der Duchamps. Ihr Ziel ist ebenfalls, einen (in Duchamps Worten) “neuen Gedanken für das Objekt” zu schaffen.

Für die elfte Ausstellung bei Essays and Observations haben wir Johannes Regin, Jonathan Monk, Michalis Pichler, Pierre-Olivier Arnaud und Roisin Byrne eingeladen, Positionen zu Appropriation Art zu zeigen, die helfen, die oftmals nicht so klaren Grenzen dieser künstlerischen Praxis zu umschreiben.

Sonja Ostermann & Matthew Burbidge

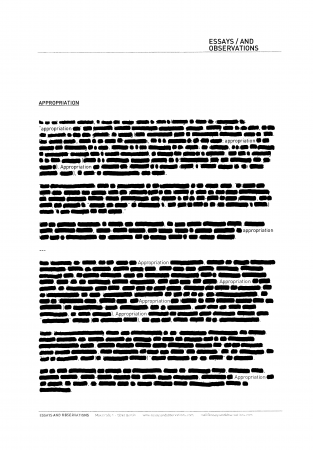

Press Release (0), "corrected" (1), "corrected" (2), "corrected" (3)