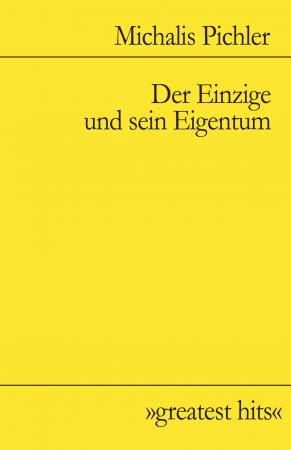

Der Einzige und sein Eigentum

Michalis Pichler, 2009

appropriation/ new vision of the manifest of individual anarchism as published 1844 by Max Stirner under the very same title (The Ego and Its Own). The chapter titles and headers have been maintained, while the main text has been edited down to include first-person-signifiers only, and a lot of white floating around it. layout, typeset and dimensions follow the German version, which has been in print almost unchanged for the last 37 years by Reclam Universal-Bibliothek.

Appropriation/ neue Vision des Manifestes, welches 1844 von Max Stirner unter demselben Titel publiziert wurde.

Die Kapitel und Seitenueberschriften wurden uebernommen, waehrend der Haupttext nur die deklinierten Ich-Konstellationen des Originaltextes enthaelt. Layout, Typografie und Dimensionen folgen den deutschen Reclam-Ausgaben des Stirner-Textes seit 1972.

464 pages, 10 x 15 cm, 2009, "greatest hits" Berlin

ISBN 978-3-86874-005-9 3-978-86874-001-1

about this book:

"How beggarly little is left us, yes, how really nothing! Everything has been removed," writes Max Stirner in Der Einzige und sein Eigentum. Everything, that is, in the case of Michalis Pichler's edition of the book, save the first person pronouns. By the grace of Pichler's conjuring, those words haunt Stirner's otherwise repressed text, floating against the white sheets of the page. Remaindered, the rendered I remains (remains to be seen).

Haunting, in fact (as Jacques Derrida notes in Spectres de Marx), is at the heart of Stirner's work. But what murder has left us with this specter avenging the desecration of the partially buried body of the text? Stirner argues that when the force of the master is removed it becomes a ghost, manifesting itself in some version of the Law. Accordingly, while both the author and God (Einziger) may be dead, we still — as Nietzsche warned — have grammar. And grammar, in turn, haunts the declensions of the reventant nouns here — a phantom limb, felt but unseen, surrounding the dismembered residium of autistic printed matter.

The possession is thus complete: demonic, obsessive, anarchic (impropre): "through a lucky chance or by stealth," "by force or ruse," as Stirner phrases it, Pichler's creative plagiarism has taken the permission of impression, of the right to print, from both Stirner and from himself. At the same time, his textual choices, his paradoxical repetition of the ostensibly unique, insists on a "corporeal ego" that cannot be removed from the defining idea of this ideal project. The most abstract, conceptual gestures must always be embodied. Here then is conceptual art as confessional lyric, the spirit and the letter, the flesh made word. It is only through the flesh, Stirner counsels, that we can break the tyranny of the mind.

—Craig Dworkin