Publishing as Artistic Practice: In Conversation With Michalis Pichler

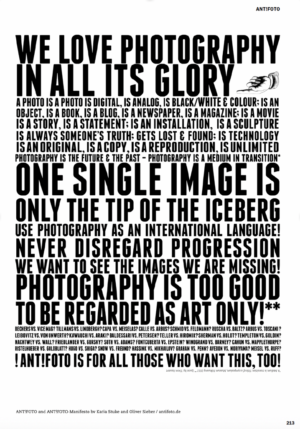

By: Victoria Hindley The founding co-organizer of Miss Read and editor of "Publishing Manifestos" surveys the vibrant landscape of art book publishing. Publishing-as-artistic-practice is thriving and increasingly mobilized by fresh voices. Given the radical changes that characterize the current global condition, much of the work in “Publishing Manifestos” — a new book that gathers texts by artists, authors, editors, publishers, designers, zinesters, and activists to explore this rapidly expanding terrain for art practice — strikes a newly resonant chord. Taken as a whole, the book gives us a kind of “indie publishers’ collective imagination” — exploring art’s capacity to speak truth to power while redefining the means of production and distribution. It’s not surprising that much of the most vital independent publishing is taking place outside the white heteronormative canon, and instead among women, queer communities, and people of color. As the editor of MIT Press’s design and visual culture list, it appealed to me to work on this book with Miss Read, Europe’s leading art book fair, because it begins to tap into the enormous field of critical independent publishing — not as the obscure background of society but as an active prodding of timely questions. At its best, publishing penetrates messy and complex questions and articulates them in ways that we can relate to and engage with. As Michalis Pichler, the book’s editor, notes below, “Publishing Manifestos” is just the beginning, but it’s an exciting one: a small celebration of the inherently irreducible plurality of values and perspectives that make up the vibrant global community of independent publishers. Victoria Hindley: When you first approached me with the idea of developing a publication on publishing manifestos, we talked about the need to overcome the Western perception that independent publishing is an Anglocentric and Eurocentric activity. As you note in the introduction, one aim of the resulting book is “to crack open the understanding of who independent publishers are, and to argue for a global perspective.” How well do you think this volume accomplishes that aim? How can we continue to push beyond the hegemonic limitations of publishing? Michalis Pichler: There is still much work to be done, but it is a step in the right direction. When I first approached you, a beta version of “Publishing Manifestos” had been published by Miss Read. While that version, put together rather hastily, reflected very well the ecosystem around Miss Read, it also had a continental bias, and I felt the need to rework it, try to open it up, and face the limitations of our viewpoint. Ricardo Basbaum and Alex Hamburger, in their dialogical “Flying letters Manifestos”, which are reprinted in the current volume, problematize limitations of this sort: “Which references? The English people have their own references — that certainly exclude ours, somehow,” says Basbaum. Other contributors tackling Western-centrism include Oswald de Andrade, Rasheed Araeen, Mladen Stilinović, Ntone Edjabe, Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, and Urvashi Butalia. V.H.: Where is the most vital independent publishing taking place today and who are some of the most vocal and effective practitioners? M.P.: There’s the pan-African platform for writing, art, and politics named chimurenga with the motto “Who No Know Go Know” (made famous by Nigerian afrobeat activist Fela Kuti). Also, Crux Desperationis, which has its base in Montevideo and is published online as an International Journal of Conceptual Writing. There’s Girls Like Us, an independent magazine based in Amsterdam turning the spotlight on an international expanding community of women from all genders within arts, culture, and activism. And, Gato Negro, based in Mexico City and part of the Rrréplica network(unruly publishers/editors/printers and duplicators México), who use the electronic stencil-printing method known as risography. Of course, there’s Temporary Services, a group of artists based in Chicago and Auburn (IN), who “strive to build an Art & Publishing practice that makes the distinction between art and other forms of creativity irrelevant.” V.H.: In many ways, choosing to publish independently is a political act in itself. You cite Adrian Piper’s concept of “aesthetic acculturation” — the way that individual artists are often subsumed by institutional systems that control resources thus requiring an abdication of creative autonomy. In publishing, you argue, this power dynamic is reversed because publishers control the means of creation, production, and distribution and thereby restore their autonomy. Can you tell us more about this role reversal? M.P.: In radical publishing, especially self-publishing and zine culture, the division of labor that Adrian Piper describes is often reversed, with artists and authors engaging in all sorts of different and un-alienated roles: creators, designers, producers, printers, publishers, and distributors. Such practices heed the call of Riot Grrrl: “We must take over the means of production in order to create our own meanings […] because we are interested in non-hierarchical ways of being.” “We must take over the means of production in order to create our own meanings […] because we are interested in non-hierarchical ways of being.” 25 years later, Temporary Services described how to “create, publish, distribute, and build a social ecosystem around your efforts.” Their model encourages the development of community around the act of publishing, which is in many ways a community effort already. Joachim Schmid, a Berlin-based artist who works with found photography, meanwhile, praises the flexibility of being able to produce work quickly, rather than being reliant on a conventional publisher’s often lengthy schedule. V.H.: What does it mean to be a politically engaged independent publisher in 2019? In what concrete ways can publishing affect change? M.P.: Quite simply, political engagement comes through the dissemination of ideas — and through the creation of an audience, a community, and a public space. According to the artist Stefan Klima, challenges fall under two categories: publishing as an explicitly political act and the desire to challenge an (art) establishment (not just an art establishment), and publishing as an implicitly political act and its challenge to imagine a new kind of reading. V.H.: The independent publishing scene is flourishing again, much in the way that it did in the 1960s in the U.S. We’ve talked a lot about publishing as artistic practice. Can you tell us more about independent publishing’s re-emergence and the related concept of artistic practice? M.P.: There are indeed parallels, but the phenomenon of art book fairs in this quantity and intensity is something new. Art book fairs today are not only a venue for representing a separate, prior publishing scene, they are also a central forum for constituting and nurturing a community around publishing as artistic practice. Miss Read Berlin and comparable events in New York, Tokyo, Mexico City, Tehran, Taipei, Moscow, London, Leipzig, Athens and elsewhere around the globe are culmination points of dispersed activities: periodically recurring meeting places in real time and real space, where people travel to gather together. We have reached a privileged historical moment when running a publishing house — or a book fair — can be valued as artwork. At the same time, it is Sozialarbeit (social work), as the post-conceptual artist Seth Price notes: “a mode of production analogous not to the creation of material goods but to the production of social contexts.” V.H.: When you queried contributors, you asked them various questions about how they sustain their passion for publishing. What answers most surprised you? M.P.: It was a surprise to run into V Vale, the legendary publisher of RE/SEARCH and Search and Destroy, in Long Island’s City Island Diner, on the way to the restroom, as he later put on record. I had been bugging him for a text for a while, by emails, which he never replied to, and by phone, where he promised to send something, but never did. And eventually he did it there, on the spot, coughing up a stream-of-consciousness manifesto, which we recorded with a smartphone, transcribed, and printed, nearly unedited, as “Humor über alles.” Art book fairs today are not only a venue for representing a separate, prior publishing scene, they are also a central forum for constituting and nurturing a community around publishing as artistic practice. V.H.: How have the massive shifts in technology changed things for independent publishers? Has technology influenced changes in the content of what we publish? M.P.: In his seminal essay “The Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin declared that “to an ever-increasing degree the work reproduced becomes the work designed for reproducibility.” If, as Benjamin argues, mechanical reproduction (in contrast to manual reproduction) destabilizes the hierarchy between original and reproduction, then digital reproduction (in contrast to mechanical reproduction) destabilizes the hierarchy between physical copy (what Benjamin calls “reproduction”) and data file. This dynamic exists for blog entries, YouTube videos, and print-on-demand books. With digital publishing, publication is located in the interface. A file is published once it has been uploaded to a distribution platform — it can be printed, to be sure, but it does not need to be. It might be read on a screen without ever setting ink to paper. During its availability (what for earlier modes of publishing we would have thought of as being “in print”), these files can be changed, without being marked as a new edition or “print-run.” Therefore, through the destabilization of the hierarchy between data file and (physical) reproduction, the status of the work becomes more indeterminate. Even though you can trace back changes and different variants with digital forensics, the authority of the source file vanishes. The same holds true for any digital artifact: there is a destabilization of the hierarchy between data files and their (digital) reproductions or alterations. V.H.: Where do we go from here? What advice do you have for up and coming independent publishers? M.P.: “Build an ecosystem around your efforts.” (Temporary Services) Michalis Pichler is the co-organizer of Miss Read: The Berlin Art Book Fair and a Berlin-based artist. He is the editor of “Publishing Manifestos,” a co-publication of the MIT Press and Miss Read.

“Don’t wait for others to validate your ideas. Do it yourself.” (Information as Material)

POSTED ON